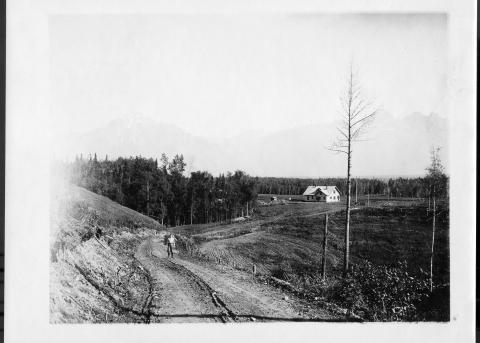

Experimental Station at Matanuska

Verso: Matanuska Valley, 1916-1930(?) Matanuska Experimental Station ca. 1920 [View down dirt road towards station, young boy in knickers on road]

Verso: Matanuska Valley, 1916-1930(?) Matanuska Experimental Station ca. 1920. [View down dirt road towards station, young boy in knickers on road]

The Hatch Act of 1887 established agricultural experiment stations across the United States and its territories to provide science-based research and support to farmers. In Alaska, these stations focused on introducing vegetable cultivars suited to the region's climate, as well as on animal and poultry management.

In 1914, the U.S. Department of Agriculture conducted a preliminary soils survey of the Southcentral region in the Matanuska Valley and approved the establishment of an experimental station in 1915. A 240-acre site was chosen just north of the Alaska Railroad, about six miles north of the Knik River and seven miles east of the new town of Wasilla. Work on the station began in April of 1917. The station’s first few years were focused on land clearing, constructing buildings, and launching research projects. Between 1917 and 1929, five structures were built that still stand today: the manager’s house, the Kodiak Cottage (originally located at the Kodiak experiment station and relocated to Matanuska in 1922), a mess hall, a dormitory, and another residence known as the Herdsman’s House.

The early research conducted at the Matanuska Experimental Station influenced the federal government's decision to designate the region as the site for one of the rural rehabilitation colonies established under Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal, aimed at alleviating the effects of the Great Depression. Created by the Federal Emergency Relief Administration, this initiative became known as the Matanuska Colony Project. Beginning in the 1930s, the project introduced approximately 1,000 new residents, including colonist families and transient workers. The influx of people spurred the need for expanded infrastructure, including additional roads and settlement areas. By 1966, the population of the Matanuska Valley had grown significantly, with an estimated 20,000 acres cleared and farmed. However, these land developments disrupted the food pathways and seasonal lifestyles of the Ahtna and Dena'ina Peoples which disrupted cultural practices (including traditional language fluency) and traditions, the impacts of which have not been fully restored to this day.