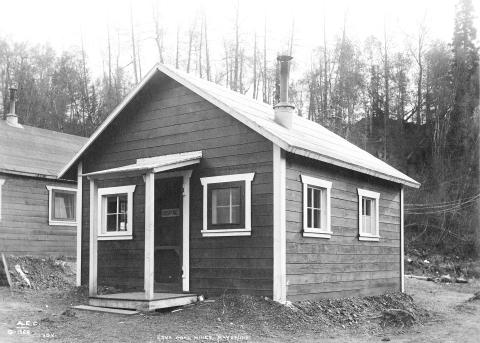

Eska Coal Mines

Eska coal mines, May 27/ 1919. AEC G1368 HGK. Verso: Alaska Railroad - Matanuska Branch, Eska [hospital at Eska] [possibly H.G. Kaiser photo]

Transcription:

Eska coal mines, May 27/ 1919. AEC G1368 HGK. Verso: Alaska Railroad - Matanuska Branch, Eska [hospital at Eska] [possibly H.G. Kaiser photo]

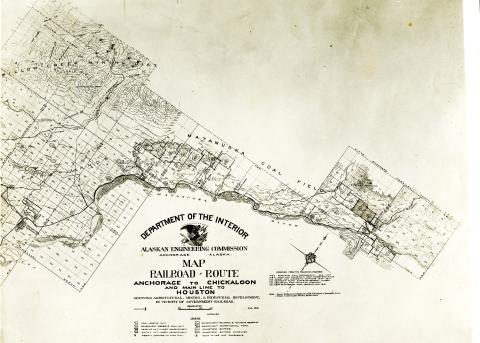

Beginning in 1898, survey crews from the United States Geological Survey identified and mapped coal fields in the Matanuska Valley along Moose Creek, Chickaloon River, and the Matanuska River (Irwin 2). The coal fields, which still exist today, cover approximately 200 square miles with the Matanuska River, which runs approximately for 80 miles, passing through it for half its distance. Within the area of the coal deposits lies several tributaries, primarily entering the Matanuska River from the north. Among them are: Chickaloon River, Kings River, and Hick’s, Gravel, Monument, Coal, Carbon, Granite, Young, Eska and Moose Creeks. The region is scenic with a valley that averages six miles wide surrounded by the peaks of the Chugach Range to the south, the Talkeetna Range to the east and the Alaska Range to the north. The lower areas of the ranges are filled with rolling hills covered in forests (Bauer 5).

Early surveys divided the Matanuska coal bed into three main fields: Chickaloon, Eska-Moose, and Young Creek. The Chickaloon field is in the lower part of the valley of Chickaloon River. It extends as far west as the Kings River, south across the Matanuska River into the valley of Coal Creek. The Eska-Moose field extends from the valley of Eska Creek to the west as far as Moose Creek. The Young Creek field lays between the Chickaloon and Eska-Moose fields, situated in the upper part of the valley of Young Creek. The coal beds found in these fields are of the Tertiary age. They are comprised of three kinds of coal: anthracite, high-grade bituminous and low-grade bituminous (Bauer A History of Coal Mining 6-7). This wide variety of coal would allow for multiple mining operations to emerge and operate simultaneously without fear of encroaching on each other’s profit potential since each type of coal served a different market.

- Bauer, Mary Cracraft. The Glenn Highway: The Story of its Past, A Guide to its Present. Sutton: Brentwood Press, 1987. Print

- Bauer, Mary Cracraft and Victoria A. Cole. A History of Coal-Mining in the Sutton-Chickaloon Area Prior to WWII. Anchorage: Alaska Historical Commission, 1985. Print.

- Irwin, Don L. The Colorful Matanuska Valley. 1968

Eska Mine

In June of 1917, to ensure that they had enough coal for their own construction and locomotive purposes, the AEC purchased the Eska Creek Mine from the Eska Creek Coal Company. On October 20, 1917, the AEC finally reached the Chickaloon field. Various spurs were constructed off the main Matanuska branch line. Among them were the Moose Creek spur, a narrow-gauged track that ran up the south side of Moose Creek, which was completed in 1923, and the Eska spur, which went up the north side of Eska Creek to the mine. Today, the town of Sutton lies where the station at the junction of the main branch and the Eska spur used to be (Bauer A History of Coal Mining 17).

From 1917 to 1918, coal was mined extensively at Eska, supplying all the needs of the AEC (Bauer A History of Coal Mining 18). It became one of the largest coal-producers in the territory from 1917 through 1920. At first, Eska Mine proved promising. The coal was nearly the quality of that found in British Columbia; so good that in Anchorage people almost mobbed the train cars, the same as they would if it was gold. The mine averaged over 150 tons of coal per day that was used to fuel locomotives, power plants and pump stations at Anchorage and Eska, as well as other places. Then came the disappointments. Mining costs proved to be higher than originally projected (from $4.50 per ton to $5.00 per ton). At about the same time the spur reached the mine, a fault sheared away a coal seam. Production plummeted. The new coal was dirty and carried a high ash content, 30 to 40 percent compared with an average for bituminous coals of 10 percent (Wilson 29). The AEC operated Eska Mine until 1920 when it became clear production was bleak and its superintendent, Evan Jones, left his position in favor of opening his own mine (Jonesville Mine) about a mile away. Not wanting to compete with a private operation, the AEC opted for closure, only opening it in times of emergency (Bauer A History of Coal Mining 26).

- Bauer, Mary Cracraft and Victoria A. Cole. A History of Coal-Mining in the Sutton-Chickaloon Area Prior to WWII. Anchorage: Alaska Historical Commission, 1985. Print.

- Wilson, William H. “The Alaska Railroad and Coal: Development of a Federal Policy, 1914-1939.” The Pacific Northwest Quarterly (1982): 66-77. Print.

The Matanuska watershed is a culturally significant place for the Ahtna Dene. It was once a bountiful region where the Ahtna could harvest salmon, moose and sheep, and served as a meeting place where the Ahtna intersected with the Dena'ina. Elder Alberta Stephan recounted that the ancestral trail system near Chickaloon River was used by so many Ahtna going past Chickaloon that the trail was three feet deep. The Nelchina gold rush of 1913 increased the number of travelers through the Matanuska Valley and expanded the ancestral Nay'dini'aa Na' Kayax trail. Starting in 1917 a federally funded railroad was constructed following our Tribe’s ancestral trail system, parallel to the Matanuska River for forty miles. The railroad and associated railroad stations, railroad spurs, coal mines (some were federally funded) and subsequent communities that developed along the railroad all contributed to the loss of irretrievable cultural resources, sites, and cultural knowledge. At least two Tribal village sites and many miles of the Nay'dini'aa Na' Kayax ancestral trail system were in the path of the railroad and were destroyed by 1925 along with several traditional salmon spawning grounds. By 1930 much of the railroad in the Matanuska Watershed was abandoned.